How the right pricing models make better products (Or — why Netflix makes really good TV shows.)

by Adam Dawkins

Money is one of the most uncomfortable topics of conversation. Maybe that’s why in business, we tend to talk so much about everything else.

Creative companies often spend a long time on their creative process, their development process, their company culture — and then, they just ‘price’ it, in a way they hope potential clients will like.

In doing this we discuss pricing as a completely separate entity to the products and services we develop.

But, what if how we price things for our clients affects the very users we build products and services for, and try to put at the centre of our development processes?

What if having a user-centric design process, development process and company culture could all be undone by the wrong pricing model?

In reality, the user experience of the products you build is directly influenced by how you charge your clients for those products.

The old adage says that ‘you get what you pay for’, but we need to add ‘and how you pay for it’.

Let me explain with an example: Netflix Originals.

Netflix Originals are incredible (and it’s because of their pricing model)

In the last few years, Netflix has transformed from a regurgitator of ancient TV series and movies to a bonafide content-maker.

As I was binge-watching my way through the latest season of House of Cards, I asked myself ‘What makes this so good? So different to TV good?’. I found three obvious components of the great user experience that relate to Netflix’s revenue model:

1. Look-No ads

This one is obvious, an episode of a Netflix Original has no ads.

Not only is my viewing not interrupted, (that’s the case with all shows on Netflix), but the show could be created for a ‘no-ads’ environment — and that’s the key. Each episode can have my undivided attention, and tell a story at it’s own pace.

Because Netflix charges me a monthly subscription, their goal half-way through an episode is only that I want to watch another episode, or that I enjoyed the episode enough to check out other programmes. These are also my goals.

In advertising-based entertainment, the goal is different, the goal is that I want to keep watching this episode enough that I’ll sit through two minutes of ads without changing channel. That’s not the same thing.

Netflix’s goal when it comes to the episode is completely aligned with my goal — enjoy the episode.

Title Sequences

I think so many networks… are afraid of a real main title sequence, it’s an old-fashioned idea, but the whole idea of a little mini-film that settles you into a world and gets you ready to experience something is a wonderful storytelling device. It frames the moment for you and gets you settled into what you’re about to take in.

—Jeff Beal, Composer, House of Cards

Netflix Originals, (and Amazon Originals) has seen the resurrection of the really good title sequences. From Narcos custom-written song (I translated it here - it relates to the content of the show really well.), to the introduction to the bleak world of House of Cards, or the really fitting intro to Black Sails on Amazon, these shows take the time to immerse me back in their world with a full-length title sequence.

Jeff Beal from House of Cards sums up the benefits of a main title sequence above perfectly. But he gets one thing wrong. Networks aren’t afraid of a real main title sequence, their pricing model doesn’t give them room to have one. They have put ads in.

This leads nicely onto point number three, but before we go there, re-read what Jeff said in the context of web development and user experience. “A title sequence gets you ready to experience something… is a wonderful storytelling device… frames the moment for you.” — that’s all great UX practice right there, made possible by Netflix’s pricing model (and made impossible by a traditional ads-based model.)

Episode length

This is a related but different point.

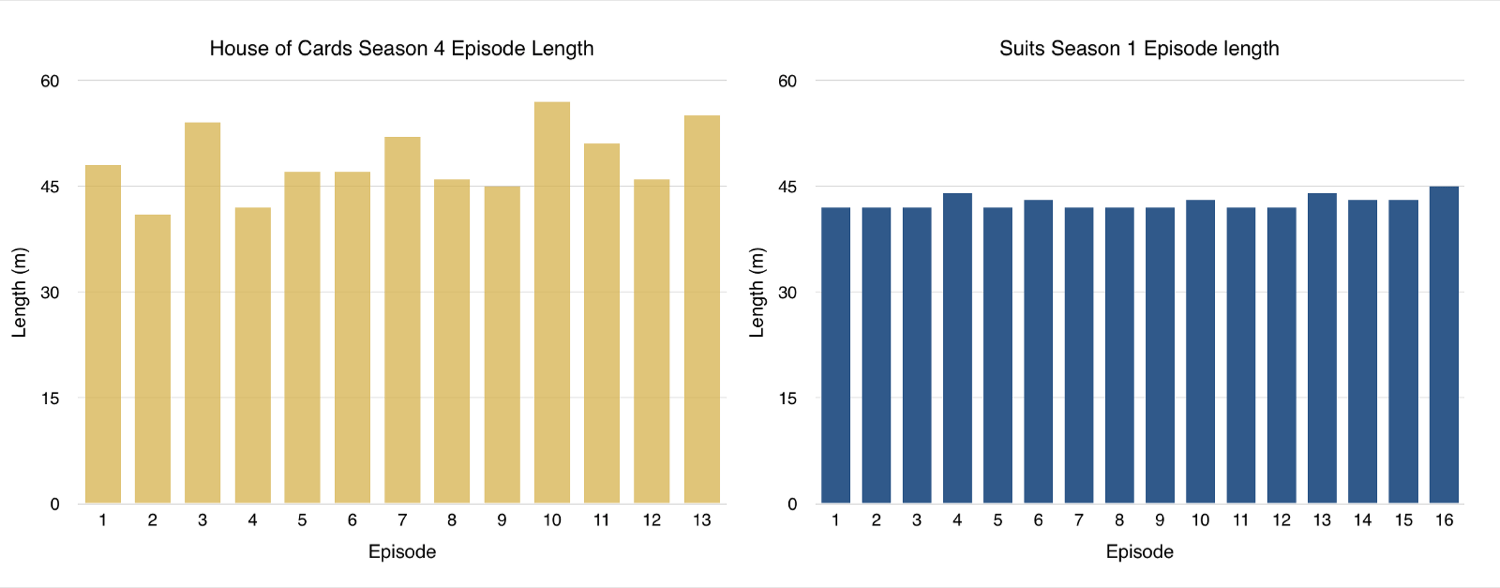

In House Of Cards Season 4, episode lengths vary from 41 minutes to 57 minutes. This 39% difference in episode length is made possible by the fact that Netflix don’t have any goals within an episode except that I enjoy the episode, and don’t cancel my subscription.

This gives creative control back to the production teams of a series to ask “What’s best for the story in this episode?”.

Contrast this with Season four of Suits, produced for television. The longest episode is 45 minutes, the shortest 42 minutes. Which is ultimately going to be a better programme? The show that has to be within 42–45 minutes per episode so that it can be cut with 25% ads, or the show that can have each episode as long as it needs to be for that part of the story?

Translating this into product-speak, the Netflix Original development agency can ask ‘What’s the best product we can make?’ — the traditional TV-style development agency asks “What can we make in exactly 42–45 minutes”.

All of this is made possible a pricing model that aligns Netflix’s goals with the user — I want to watch good shows, they want me to pay to watch their shows. So make good shows.

How to do User-centric Pricing

There are only so many ways to skin the proverbial cat of pricing, but what would ‘user-centric’ pricing look like? Like with most things that relate to the User Experience, there’s no one answer — context is key. We haven’t figured all of this out yet, but here are a few thoughts:

Revenue Sharing on Revenue-based Goals

For anything related to a tangible user goal, e.g. completing a checkout process, signing up to a form, a profit share model makes a lot of sense, because we get a three-way alignment between user, agency and client.

That’s the approach we’re taking on Rebound, our checkout recovery solution (coming soon). Most customers that start a checkout want to buy something, our clients want them to buy it; by taking a revenue split on these failed checkouts, that’s also exactly what we want. We’re all in agreement.

Iterative, time and materials pricing for the big and the new

On large or brand new product ideas, sprint-based pricing allows the development agency to keep iterating by testing against the user experience, without the artificial constraints of early guesstimates and fixed prices.

Priced on value, so that it exists

This is perhaps the approach that could risk affecting the user’s experience the most, as all three parties’ goals aren’t directly aligned, but when we do fixed price projects, we’re careful to build in value for our client, and enough time for us to focus on the user in our development cycle.

Partnerships

We haven’t explored this one yet, but a partnership-model that moves beyond isolated projects allows clients and agencies to work together in on a user-first journey of discovery. That’s an exciting idea.

Conclusion: User-centric to the core

To build great products, you need to put the user at the centre, and to truly put the user at the centre, she needs to be considered at every level of your business; including how you price things. If Netflix Originals has shown us anything, it’s that crafting a truly excellent user experience takes time, skill and attention to detail, and that even your pricing model could get in the way.

The best part, of course, is that if you price your work in a way that improves the user’s experience — you just got more valuable for your clients too.

Win-Win-Win.

Thanks

A few special mentions for this article:

- Thanks to Paul Boag for his excellent presentation on breaking down silos within businesses and putting the user first throughout the whole organisation at Digital Dumbo; A large part of the inspiration for this thought-explosion.

- Thank you to Andy Budd, who chatted pros and cons of various pricing models. It was very useful.

- Thanks to Iggy Hammick and Digital Dumbo London for the event for which the other two thank you’s were made possible.

- Jeff Beal’s thoughts on title sequences comes from Episode 7 of Song Exploder, where he takes apart the House of Cards title sequence — Song Exploder is a podcast where musicians take apart their songs, and piece by piece, tell the story of how they were made.